Special section Soft tissue sarcomas

Definition

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) are a heterogeneous group of malignant tumors that originate from primitive mesenchymal tissue.

STS account for 7 % of all childhood cancer.

Histologic appearance is as mature mesenchymal tissue, but topic could be different.

STS are divided into two groups based on a histologic type:

-

rhabdomyosarcoma:

- embryonal

- alveolar

- pleomorphic

- non-rhabdomyosarcomatous STS (NRSTS)

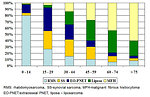

Morphologically there are many different types of STS (more than 40 histologic subtypes of STS) (Figure 1).

STS can develop almost anywhere in the body and may occur in any age.

Epidemiology

Annual incidence of STS in childhood is 0.6–0.8 : 100 000 with slight predominance in boys (M : F = 1.4 : 1)

The most common and typical pediatric STS is rhabdomyosarcoma (a tumor of striated muscle), it accounts for 50 – 60% of tumors in age group 0 to 15 years.

NRSTS account about 3% of all childhood tumors, this heterogeneous group includes tumors of:

- connective tissue (liposarcoma, desmoid…)

- peripheral nervous system (malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor)

- smooth muscle (leiomyosarcoma)

- vascular tissue (angiosarcoma)

In pediatric age synovial sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, fibrohistiocytic tumors and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are more frequent types of NRSTS and typical for adolescent age.

Distribution of histologic types of STS is age specific with bimodal age distribution: (Figure 2):

- the first peak is at the age 2 to 6 years, dominate rhabdomyosarcoma

- the second peak is at adolescent age with predominance of NRSTS

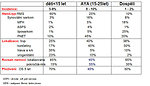

Localization of STS also depends on the age. STS in infants and toddlers generally involves the head and neck or genitourinary areas. Adolescents more commonly develop STS on extremities, truncal or paratesticular region (Figure 3):

-

head and neck (40% of STS):

- orbita (10%)

- non parameningeal: stoma, larynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, gl. parotis

- parameningeal (20%): middle ear, paranasal sinuses, nasopharynx, nose fossa pterygopalatinea

-

genitourinary (25%) :

- prostate/urinary bladder (15%)

- paratesticular (6%)

- vagina, cervix, uterus (2%)

- extremities (20%):

-

others (30%):

- chest wall (10%)

- retroperitoneum

- hepatobiliary tract (3%)

- paraspinal region

- perineum (2%)

Etiology and etiopathogenesis

The exact cause of STS is not entirely known, the most of STS is sporadic with no identified risk factor.

Some genetic factors and hereditary syndromes have been associated with an increased risk of developing STS:

- Li Fraumeni syndrome

- Gorlin syndrome

- Beckwith- Wiedemann syndrome

- Neurofibromatosis type I

- Werner syndrome

- RB1 gene mutation

- Familiar adernomatous polyposis and tuberous sclerosis

Environmental factors associated with risk of STS development:

- radiation induces STS (account about 2-5% of all STS)

- Epstein-Barr virus infection

- HIV infection

- chemicals (arsenic, PVC)

- children of mothers who smoke marihuana have a threefold increased risk to develop STS

Clinical presentation and symptoms

STS affect tissues that are elastic and easily moved, therefore tumor may exist for a long time before being discovered.

Clinical presentation and symptoms depend on localization and size of the tumor.

- the first and most common presenting symptom is palpable/visible painless tumor mass or lump

- depends on localization the first symptom could be also malfunction or difficulty to use extremity or other part of the body

- local pain, swelling, redness appears later

- systemic symptoms (e.g. fever, weight loss, night sweats) are rare

Head and neck localization especially in infants and toddlers (Figure 4):

- soft tissue mass, hoarseness, dysphagia, local pain

- cranial nerve palsy, sinusitis, nasal discharge, epistaxis

- chronic otitis media, purulent blood-stained ear discharge

- diplopia, nasopharynx ostruction, proptosis, strabismus, ocular palsies

Genitourinary localization:

- micro/macroscopic hematuria, dysuria (Figure 5)

- urinary obstruction, recurrent urinary tract infections

- vaginal bleeding, grapelike clustered mass protruding through vaginal opening

- painless paratesticular mass

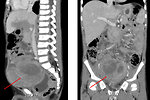

Abdominal localization:

- asymptomatic for couple of months (Figure 6)

- abdominal dyscomfort and pain

- intestinal obstruction, ileus

- urinary obstruction

Extremities:

- the first symptoms is palpable lump, initially painless

- later on pain of involved area

- limping, walking difficulties (Figure 7)

Up to 20% of patients have symptoms of metastases (bones, bone marrow, lung, lymph nodes). Visceral metastases (liver, brain) are rare except pre-terminally disease.

Diagnostic procedures

Diagnostic procedures are the same regardless of the age and histologic type of STS. Patient should be sent to a specialized center already in suspected STS. Initial work up and further management needs a lot of experiences. The diagnostic evaluation should delineate the extent of the primary tumor and the extent of metastatic disease.

Physical examination:

- examining always undressed patient

- measurement of primary tumor

- assessment of regional lymph nodes

- careful neurologic examination

Imaging studies:

X ray: the role of X-rays is limited mainly to looking for metastatic spread to the lungs or mediastinal lymph nodes (Figure 8).

Ultrasound: can be used for the first orientation regarding primary of the abdominal/pelvic tumors, to see if tumors in the pelvis (such as prostate or bladder tumors) are growing or shrinking over time.

CT scan: is useful for intrathoracic, intraabdominal, retroperitoneal or pelvic STS as well as parameningeal rhabdomyosarcomas. This test can often show a tumor in detail, including how large it is and if it has grown into nearby structures. It can also be used to look at regional lymph nodes, as well as the lungs or other areas of the body where the cancer might have spread (Figure 9)

MRI: is preferred for STS localized at extremities, chest wall, head and neck or pelvis/perineum. MRI scans can help determine the exact extent of a tumor, because they can show the muscle, fat, and connective tissue around the tumor in great detail. This is important when planning surgery or radiation therapy. Also is very useful for parameningeal STS to exclude the spinal cord or brain metastatic spread (Figure 10).

18 FDG PET scan: is useful adjunct in the initial staging of STS for detection of metastases. 18 FDG PET scan sensitivity for rhabdomyosarcoma is 83%, specificity 97%. PET scan can be used for evaluation of tumor response to chemotherapy and for follow up study to detect relapse/progression of disease (Figure 11).

Bone scan: can help to verify metastatic spread of sarcomas to the bones. This test is useful because it provides a picture of the entire skeleton at once.

Aspiration and trephine bone marrow biopsy is part of the initial work up to exclude bone marrow involvement (positive in approximately 28% of cases).

Laboratory tests:

- complete CBC, ESR, coagulation profile

- serum biochemistry, liver function tests, urea, creatinine, uric acid, ALP

- LDH, (non-specific tumor marker, parameter of tumor burden)

- the is no specific tumor marker for STS

- chimeric fusion proteins in peripheral blood as minimal residua disease detection

Examination of tumor tissue after biopsy or primary resection is mandatory for accurate diagnosis and risk stratification.

-

histology: morphology of tumor cells and immunohistochemistry to determinate subtype of sarcoma (Figure 12)

- proliferative activity – Ki67 index, angioinvasion

- mandatory is information regarding resection margins

- cytogenetics and molecular genetics: to detect specific chromosomal translocations and chimeric proteins. It is important for accurate diagnosis and minimal residual disease detection (Figure 13)

- tumor microenvironment : tumor infiltrating lymphocyte, tumor associated macropaghes, PD-L1 expression

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis depends on primary localization of the tumor and age of the child.

It is necessary to exclude:

- non-malignant processes (inflammation, post-traumatic conditions, myositis ossificans, hematoma, congenital anomalies)

- benign tumors (lymfangioma, hemangioma, lipoma, fibroma, neurofibroma, hamartoma)

- other malignant tumors ( lymphoma, germ cell tumor, neuroblastoma, bone sarcoma…)

Therapy

Treatment of sarcomas is multidisciplinary, requires the integration of all three basic modalities – surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Figure 14).

Surgery:

- surgery is treatment of choice in low grade sarcomas

- for high grade sarcomas (rhabdomyosarcomas) the main goal of surgery is radical resection of the tumor with sufficient margins of normal tissue (at least 1 cm), but not mutilation

- if the tumor cannot be resected, an initial biopsy is performed

- delayed radical surgery is performed after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for initially unresectable tumors

- clinically suspicious lymph nodes should be excised at any site

- routine sampling of regional lymph nodes is appropriate for most sites

- dissection of regional lymph node did not improve survival and therefore is not generally recommended

Chemotherapy:

- chemotherapy is indicated for all rhabdomyosarcomas regardless of the clinical stage (it differs only in intensity and duration of the treatment)

- NRSTS are considered to be less chemosensitive than rhabdomyosarcoma, but chemotherapy improved overall survival and therefore is recommended for all pediatric NRSTS

-

Intensity of chemotherapy is based on risk stratification according to:

- histologic type of sarcoma ( RMS or NRSTS)

- extent of disease (clinical stage, localized or metastatic disease)

- IRS group

- primary localization of the tumor and age of the patient

- high dose chemotherapy did not improved overall survival and currently is not a part of standard treatment

Radiotherapy:

- as a local treatment is crucial for local control of sarcomas, especially for IRS group II

- for IRS group IV (metastatic STS) patients receive radiotherapy to the primary tumor and metastatic sites

- rhabdomyosarcoma is only moderately radiosensitive, for this reason high dose of radiation is recommended (50 Gy) and could not be less than 40 Gy

- brachytherapy has in pediatric oncology very limited indications

- the main problem of radiotherapy is high prevalence of late toxicity, especially for infants with STS on the head and neck. Therefore the age and location of the tumor are limiting factors for radiotherapy indication

- radiotherapy is always given to the undersigned informed consent of the child’s parents

Prognosis and outcome

Factors influencing prognosis:

- age ( >10 years is negative prognostic factor)

- grade of malignancy, type of sarcoma

- location of the tumor (extremities vs central)

- extent of disease (clinical stadium)

- size of the primary tumor ( >5cm)

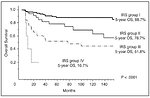

- IRS group ( I – IV)

5-year overall survival according to IRS group (Figure 15):

- IRS I - 88.7% (complete resection)

- IRS II - 78.7% (microscopic residual tumor)

- IRS III - 51.8% (macroscopic residual tumor)

- IRS IV- 16.7% (metastatic disease)

Author: Viera Bajčiová, MD, PhD