Special section Malignant melanoma

Definition

Malignant melanoma in children and adolescents is a rare disease; nevertheless it is the most common type of skin cancer in this age group. Only 1–4% of all the cutaneous malignant melanoma in the population consists of patients younger than 20 years. Pediatric melanoma is generally defined as melanoma occurring in the age from birth until the age of 21 years of age. According to the age melanoma is divided into four groups:

- congenital melanoma ( diagnosed in utero prenatally and at the birth)

- neonatal/infantile melanoma (from the birth to 1 year of the age)

- pediatric melanoma (from 1 year to 13 years)

- adolescent melanoma ( from 13 to 21 years)

Some authors divide pediatric melanoma into two groups – prepubertal and postpubertal or melanoma under 10 years of age and over 10 years.

Epidemiology

Malignant melanoma is among the tumors with fastest rising incidence of tumors and occurrence is shifted to younger age groups.

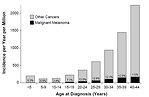

For children under 15 years is an annual melanoma incidence increase of about 1% per year, in adolescents 7% a year and in young adults up to 24 years the annual incidence increase is of 12% (Figure 1).

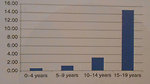

According to the WHO definition for rare tumors (incidence less than 5 : 100 000) include melanoma in children below 12 years of a rare cancer, but melanoma in adolescents has not. (Figure2).

In adolescents is a significant predominance of melanoma in girls with predominant localization on the upper and lower extremities and trunk.

For children under 5 years of age, melanoma is more common in boys, in which dominates the appearance of the head and neck.

Etiology

The causes of cutaneous malignant melanoma in children are mostly unknown. More vulnerable are the children of low skin phototype (white skin, freckles, blond or red hair) (Figure3). Malignant transformation may occur spontaneously. Several risk factors may be associated with melanoma development.

- ultraviolet solar radiation: is the best known risk factor for cutaneous malignant melanoma due to genotoxic effect of UV rays. More than a cumulative dose applies to the quantity and size of the intermittent sunbathing. Most at risk are individuals with skin phototype I and II. Child's skin is more sensitive to UV radiation, it is thinner than adult skin and can therefore be considered a risk phototype. For these reasons, infants under 6 months of age not to be exposed to UV solar radiation. Older children should use a suncream with a high UV filter.

- familial occurrence of pediatric melanomas is expected in a case with positive family history and age <6 years of the child. Familial melanomas are autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance, occur at younger age. 10-25% of familial melanomas demonstrated germline mutations in the genes CDKN2A (cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A) or CDK4 (cyclin dependent kinase 4).

-

pigmented nevi: there is a wide spectrum of pigmented skin nevi in childhood, undergoing constantly changes in size, color and surface from birth to puberty.

- Intradermal nevi without breaking the junctional zone are the most common. In the course of life are fixed with no risk of malignant transformation, and they should not be removed. Excision is indicated only in a case of traumatized nevus.

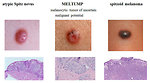

- Juvenile Spitz nevus is a special form of nevus occurs in children aged 3-13 years, arises from normal skin. It is hemispheric, rigid, smooth with a relatively fast growth (2-3 months). A typical Spitz nevus does not pose any risk, but there are also atypical Spitz nevi and malignant or transitional forms. The distinction between atypical Spitz nevus and spitzoid malignant melanoma is difficult (Figure4).

-

genetic factors: some hereditary disorders associated with high risk of melanoma

- Xeroderma pigmentosum is autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by excessive photosensitivity to ultraviolet radiation. Multiple skin tumors and melanomas are frequent in young age. Median of melanoma occurrence is 19 years typically localised on the head and neck.

- germinal mutation RB1 gene is associated with higher risk of skin melanoma

- Werner syndrome is autosomal recessive hereditary syndrome cause by mutation of WRN gene. Characterized is by unusual localization of melanoma (nasal cavity, sole of the foot)

- Dysplastic nevi syndrome is je autosomal dominant hereditary disorder characterized by dozens of skin dysplastic nevi (50 and more) and/or 5 and more atypical melanocytic nevi and melanoma in family history.

- neurocutaneous melanosis is rare disease characterized by large congenital melanocytic nevus (> 9cm) or multiple congenital nevi (>3) and leptomeningeal proliferation of melanocytes. Neurology symptoms occur within 2 years of the age. Leptomeningeal melanoma with poor prognosis develops in 64% of patients. (Figure5)

- Li Fraumeni syndrom is autosomal dominant hereditary syndrome, cause by mutation of tumor suppressor gene TP53 (17p13). Patients are at high risk to develop different types of malignancies including melanoma.

- immunodeficiency: patients with congenital immunodeficiency, childhood cancer survivors or patients on immunosuppressive therapy due to organ transplantation are 2 – 6 times higher risk of developing melanoma

Most malignant melanomas in prepubertal children and adolescents arises de novo in healthy individuals who have any of these risk factors.

Clinical presentation and symptoms

Clinical symptoms of melanoma are non-specific and there are a number of skin lesions in children that may mimic malignant melanoma (benign nevi, dysplastic nevi, atypical blue nevus, hemangioma, pyogenic granuloma, verrucas, Spitz nevus etc.). Prepubertal melanoma has not always typical appearance of melanoma, as is known from the adult oncology.

In preexisting pigmented skin affections the most common symptoms of melanoma are known ABCDE criteria (Figure6). These criteria pediatric melanoma may not always apply and can sometimes be misleading. Benign nevi can grow with the child and is increasing, while at the same time healthy skin may appear a tiny little melanoma. Conversely, a dark pigmented nevus, which has a child from birth, it can vary in its deeper parts change and melanoma may be visible on the surface.

Local symptoms: ABCD criteria for preexisting nevus. Itching, tingling, enlargement of nevus, ulceration, bleeding.

Systemic symptoms: are caused by metastatic spread (anorexia, weight loss, unexplained fever, lymphadenopathy, caugh, hepatosplenomegaly.

Diagnosis pediatric melanoma, even when appearance of clinical symptoms (itching, tingling, a gradual rise or ulceration) is often unexpected and surprising.

Diagnostic procedures

Diagnosis of pediatric melanoma is arduous due to the rare occurrence, the absence of well-known risk factors, atypical presentation and many other skin nevi. In comparison with the adult population have melanoma in children and patients under 20 years of age usually greater size and thickness.

Nearly 80% of pediatric patients are diagnosed with localized disease. The lymph nodes is demonstrated in 15-30% of patients, and less than 5% of patients have distant metastases at the time of diagnosis.

Clinical examination: for correct diagnosis is mandatory a detailed examination of the entire skin surface including the scalp and photodocumentation of all suspicious lesions. Dermatoscopic examination of suspected lesion is crucial (Figure7).

Imaging studies and laboratory tests for pediatric melanoma do not differ from the examination of adult patients. Imaging studies are focused not only on locoregional extent of disease, but also to detect metastatic disease. Extent of locoregional disease is crucial for further treatment.

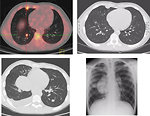

Whole-body 18FDG PET examination significantly contributed to a more accurate diagnosis in fusion with CT scans (Figure8).

Histopathology of pediatric melanoma: pediatric melanocytic tumors should be divided in to 3 categories:

- conventional skin melanoma

- melanoma origin from the large congenital melanocytic nevus (risk of transformation to melanoma is 5–10% usually within the first 10 years of the life

-

spectrum of spitzoid melanocytic tumors:

- typical (benign) Spitz nevus

- atypical Spitz nevus

- MELTUMP

- spitzoid melanoma

Definitive diagnosis of melanoma is in the hands of pathologist and molecular biologist.

Histopathology report evaluates:

- type of melanoma (nodular, superficially spread melanoma, lentigo maligna or acrolentiginous melanoma). For pediatric age is typical nodular or superficially spread melanoma (Figure9)

- safe surgical margins ( at least 0.5–1 cm)

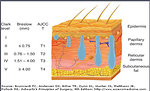

- thickness (Breslow), microscopic invasion according to Clark (Figure10)

- ulceration, lymphangioinvasion, microsatellites

- tumor microenvironment ( tumor infiltrating lymphocytes CD8, CD4, CD3, macrophages, microvascular density, PD-L1 expression) is important for decision regarding immunotherapy

Molecular genetic examination: Malignant melanoma is a tumor with the broadest spectrum of signaling pathways mutations. Molecular genetic factors influencing the biological behavior of melanoma in different age groups. Typical genetic mutations described for melanoma are germline mutations CDKN2A gene, RB1 gene, CDK4 and MC1R (melanocortin-1 receptor) gene, TP53 and somatic mutations of BRAF, RAS, KIT (Figure11).

Molecular genetic examination is important for:

- exact diagnosis of pediatric melanoma: biological studies can help in the differential diagnosis of melanocytic lesions and spitzoid forms of melanoma in a case of unclear histopathological examination

-

to determinate the exact origin of pediatric melanoma:

- total absence of B-RAF mutation in spitzoid lesions contrasts with the high incidence of this mutation in conventional melanoma (53–80%) and melanocytic nevi (25 - 50%). This fact also supports the theory of a different developmental path of spitzoid lesions.

- NRAS mutations occur in adult melanoma in 15–20% . In children are more frequent in melanoma origin from congenital melanocytic nevus

- to determine use of targeted therapy for advanced melanoma

Treatment

Treatment of pediatric MM is built on the experience of treatment of melanoma in the adult population and is not different from guidelines recommended in adult oncology. Challenge in pediatric oncology is almost absolute lack of pediatric clinical studies and the lack of any reduction in the age limit for enrollment to adult studies.

Surgery

Localized melanoma is surgical disease and radical surgery with safe margins is treatment of choice.

Thickness of primary melanoma lesion determinates the width of safe margins (for melanoma thickness <2 mm safe margin is 1cm, for thickness of > 2 mm is safe margin 2 cm). These principles apply to all ages.

Resection of sentinel lymph node in children is realized for melanoma with thickness below 1 cm, if the surface is ulcerated and melanoma with high proliferative activity

For spitzoid melanocytic lesions surgical guidelines are similar or same as for melanoma

In a case of positive sentinel lymph node dissection of regional lymph nodes is recommended

Chemotherapy

Malignant melanoma is considered to be a chemoresistant tumor and the role of chemotherapy is limited.

Monotherapy (dacarbazine) historically reached overall therapeutic response in less than 20% of patients with no effect to overall survival.

Combination of chemotherapeutic agents (combination DTIC + VBL or DTIC + Cisplatina) reach response rate only in 10–20%, of patients. Duration of response do not exceed 4–6 months

For advanced pediatric melanoma temozolomide was under clinical study.

Targeted biology therapy

Identification of specific oncogenic mutations leads to the development of targeted biology therapy.

The most frequent mutation (positive in > 55%) in conventional melanoma is BRAF V600E mutation. Specific monoclonal antibodies (vemurafenib, dabrafenib) are approved for advanced melanoma since 2011. Antibodies demonstrated in a randomized trial of advanced melanomas significantly longer survival (84% vs. 64%). Currently there is only one pediatric clinical trial with vemurafenib for children with advanced melanoma, lower age limit is 12 years.

Sorafenib, multikinase inhibitor (BRAF,CRAF,VEGF and PDGF) has been tested in adult oncology, but no studies were realized for pediatric population.

Immunotherapy

Interferon alfa: is the longest used method of immunotherapy for stage III melanoma. It has been a standard treatment of adult melanoma for years, but with limited effect. The overall response rate was around 15 - 20%. According to current guidelines of COG (Children's Oncology Group) it is still considered the standard method of treatment for advanced pediatric melanoma

Interleukin 2 was used for metastatic melanoma with response rate 10–20%. Its utilization for pediatric patients limited poor tolerance and severe toxicity.

Tumor vaccines were assumed to increase immunological detection of tumor cells and strengthen the anti-tumor immune response. Different types of vaccines have been tested (anti-idiotypic vaccines, DNA vaccines, dendritic cells). Their preparation is required highly individual approach, financial demands and strict laboratory conditions. In pediatric oncology vaccines are not yet a part of standard therapy (Figure12).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors:

- Ipilimumab (human anti CTLA4 antibody, CTLA-4 = cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4) showed in a prospective randomized study significant prolongation of life in metastatic melanoma. Its use in pediatric oncology have been delayed nearly 4 years, currently four pediatric clinical studies have been open for pediatric advanced melanoma.

- Anti PD-1 monoclonal antibody (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) are humanized monoclonal antibodies against receptor PD-1 (programmed death receptor) (Figure13)

Prognosis and outcome

Prognosis of pediatric malignant melanoma is difficult to predict. Extent of disease (clinical stage) is an independent prognostic factor regardless of age.

Negative prognostic factors in children are:

-

clinical factors:

- age (infantile melanoma and age > 10 years)

- central localization (head and neck, trunk)

- pathology factors:

- type of melanoma (nodular melanoma, amelanotic melanoma)

- thickness (Breslow)

- ulceration, lymphovascular invasion

- high proliferative aktivity (high Ki67 index)

- positive sentinel lymph node

- negative BRAF mutation (Figure14)

- biology factors:

10-year overall survival:

- stage 1 is 94%

- stage 2 is 79%

- stage 3 is 77%

- stage 4 is less than 10%

Author: Viera Bajčiová, MD, PhD