Special section Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Definition

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) represents a heterogeneous group of malignant neoplasms of the lymphoid tissues or lymphatic system (lymph nodes, lymphatic vessels, lymph and lymphatic organs – tonsils, spleen, thymus, bone marrow, appendix, Peyer’s patches in the abdomen) (Figure 1)

NHL should derived from B cell progenitors, T-cell progenitors, mature B or T cells

Pediatric NHL is a systemic disease (because lymphatic tissue is found throughout the body)

The most common type of pediatric NHL differs from NHL in adult population with respect to:

- epidemiology and etiology

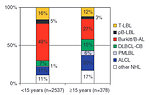

- histologic subtypes (Figure 2)

- biology and clinical behavior

- staging system

- treatment and outcome

The key features for definition of histologic subtypes of NHL is

- size and shape of the cells (large or small)

- growth pattern ( may be diffuse or follicular)

- cytogenetics and surface markers (T or B cells)

The most common types of pediatric NHL belong to one of three main types:

- lymphoblastic lymphoma (usually T cell)

- Burkitt lymphoma

-

large cell lymphoma:

- diffuse large B-cell, DLBCL

- anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALCL

Almost all pediatric NHL are high grade malignancies with diffuse pattern of growth

Low grade NHL (follicular lymphoma, MALT lymphoma, primary CNS or cutaneous lymphoma) typical for adult population are rare in childhood and account less than 10 % of all pediatric NHL.

Epidemiology

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the fifth most common pediatric cancer and accounts approximately 7 % of all malignancies in children less than 15 years of the age

Peak incidence is in adolescent age, median age at diagnosis is 10–12 years and it is very rare in infants.

Annual overall incidence is about 10 : 1 million, but incidence is age dependent:

- children < 5 years 2.8 : 1 million

- 5 – 9 years 8.8 : 1 million

- 10 – 14 years 14.3 : 1 million

- 15 – 19 years 21.8 : million

There is a male predominance, M : F ratio is 2–2.5 : 1

Incidence and distribution of specific NHL types differs by:

- age (more common in older children and adolescents) (Figure 3)

- race (more common in white than in black children)

- geographic region (high incidence of endemic Burkitt lymphoma in equatorial Africa)

Etiology and etiopathogenesis

For the most cases of pediatric NHL the exact cause remains unknown.

Several risk factors have been recognized:

-

Association with immunodeficiency: congenital immunodeficiency syndromes

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

- ataxia teleangiectatica

- Bloom syndrome

- X-linked lymphoprolopherative syndrome

-

Association with hereditary predisposition syndromes:

- Nijmegen-breakage syndrome

- Congenital deficit of mismatch repair gene syndrome (CDMMR syndrome)

-

Secondary immunodeficiency:

- organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressive therapy

- AIDS

-

Infectious agents :

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) chronic infection play a significant role together with malaria infection in endemic Burkitt lymphoma in Africa, in the Europe the role of EBV infection remains unclear

- HTLV-1 virus

- Hepatitis C virus

-

Environmental factors:

- secondary NHL after radiation exposure or chemotherapy

- chemicals (pesticides, herbicides, organic chemicals) plays minor role in pediatric NHL

- Familial occurrence of NHL is very rare, there are no known risk factors to explain familial occurrence of NHL

- High birth weight (over 4000 gr) and older mothers (> 40 years of the age) may be a risk factor for NHL development

Clinical presentation and symptoms

Children with NHL may experience many symptoms depend on the localization, size and rapid growth of NHL. Symptoms are usually not specific and progressed rapidly within several days.

Local symptoms

- Lymph nodes: painless swelling of lymph nodes progressing in size, usually detected in peripheral lymph nodes (neck, supraclavicular area, axilla or groin) or usually asymmetric tonsillar hypertrophy

- Mediastinum: is typical localization for T-cell lymphoblastic NHL, 10–15% of primary mediastinal NHL is DLBCL. Typical symptoms are dry cough, shortness of breath, dyspnea, orthopnea, breathing difficulties and typical symptoms of vena cava superior syndrome (SVCS)

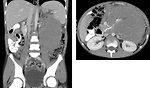

- Abdomen: infradiaphragmatic lymph nodes and/or organ involvement (typical intestinal involvement in ileocecal region) is characteristic for B-cell NHL. Initially patient feels full, with or without abdominal distension or abdominal pain. Frequently the first symptom of abdominal NHL is acute abdomen due to intestinal invagination or obstruction. Sometimes may be the first symptom of NHL oliguria or anuria with acute renal failure due to acute tumor lysis syndrome. Sometimes also other (non-lymphatic) parenchymal organs should be infiltrated by NHL (kidneys, pancreas) (Figure 4)

- Skin: symptoms are not specific, usually in form of itchy, red or purple lumps or skin nodules, not healing and progressing in time despite local dermatology treatment. (Figure 5)

- CNS: primary CNS NHL presented with headache, visual disturbances, speech problems, focal neurological signs and cracial nerve palsies or seizures.

Systemic symptoms

Child with NHL is moderately to severe ill, 20–30% patients may present with systemic symptoms:

- Fever > 38 °C and chills

- Sweating (particularly at night)

- Unexplained weight loss

- Symptoms caused by low leukocytes counts: anemia, general weakness, frequent and recurrent infection, petechiae and bleeding

Diagnostic procedures

Physical exam

Special attention must be paid to the lymphatic system and all symptoms mentioned above with special attention to lymph nodal areas, hepatosplenomegaly, any palpable mass, breathing or other difficulties.

Involved lymph nodes are not painful or tender, but have a “rubbery” firmness to palpation. Waldayer’s ring involvement by NHL may present as asymmetric tonsillar enlargement (Figure 6). Therefore visual examination of the nasopharynx, oropharynx is important. In boys is essential to palpate both testicles due to high risk of testicular infiltration by NHL.

Laboratory tests

There is no specific blood test that indicates NHL. Tests include:

- hematology tests: ESR, CBC, coagulation profile including D-dimer to exclude disseminated intravascular coagulopathy or sepsis elevated ESR is common marker of disease activity

-

biochemistry:

- liver tests, urea, creatinine uric acid, CRP

- LDH, (serum level of „LDH has a prognostic significance)

- total protein, albumin, ionogram

- biochemistry is important for monitor of tumor lysis syndrome

- cytogenetic and molecular genetic studies are important for exact diagnosis of NHL subtypes. Each histologic subtype of NHL is characterized by one or more molecular alterations/mutations. Many of these alterations are chromosomal translocations. Molecular genetic analysis is also important for evaluation of so called minimal residual disease (Figure 7)

Imaging studies

Because NHL is systemic disease, imaging studies are important to detect extent of disease necessary for clinical staging and further management.

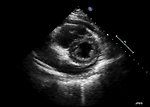

Ultrasound: of all nodal areas, abdomen and testicles is usually the first imaging study. Ultrasound can show the structure of lymph nodes, areas of necrosis, vascularity and L/T index. Echocardiography is mandatory for pericardial effusion evaluation (Figure 8)

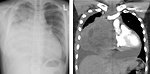

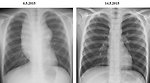

Chest X-ray: (posteroanterior and lateral) to assess for possible mediastinal mass, deviation of airways, cardiac shadow and lung infiltration. (Figure 9)

CT scan: of the chest, abdomen and pelvis is the part of initial work up for NHL. CT scan of the brain is useful to exclude brain parenchyma or meningeal infiltration or CNS bleeding (Figure 10)

MRI: is not used as often as CT scan for diagnosis of NHL. MRI could be useful for diagnosis of CNS infiltration (brain or spinal cord) in children with neurologic symptoms.

18 FDG PET scan: usually in fusion with CT (PET/CT scan) is useful to verify initial extent of disease in the whole body and measure activity in the tumor involved areas (SUV) as well as for tumor response evaluation. 18FDG PET/CT is beneficial for follow up study to evaluate residual masses, diagnosis of early recurrence.

Histopathology

Biology material has to be send to several laboratories:

- pathology for morphological and immunohistochemistry investigation,

- flow cytometric analysis for lymphoma subtyping (immunophenotyping) based on detection of antigens on lymphoma cells surface

- cytogenetic analysis (fluorescence in situ hybridization, FISH and polymerase chain reaction, PCR) (Figure 11)

The same tests have to be done not only from tumor mass, but also from bone marrow, cerebro-spinal fluid or effusion (pleural, pericardial or ascites).

Several classification systems have been used for NHL (Kiel classification, NCI working classification, REAL classification). Classification of NHL was changed several times. For pediatric NHL is classification used for adult NHL very complicated, therefore pediatric NHL are usually in clinical practice divided into three major groups (Figure 12).

Burkitt lymphoma: is an aggressive type of NHL in children, represent 40–50 % of pediatric NHL

- occurs as a sporadic (Europe, USA), endemic (Africa) and immunodeficiency-related tumor cells are mature B cells, with CD20, CD19, HLA-DR positivity

- typically occur in boys at the age 5–10 years

- it is considered one of the fastest growing cancer (the doubling time = the number of tumor cells doubles) is 24 hours !!

- more than 90% of B-NHL have typical translocation t(8;14)

- 90% of mature B-NHL is localized in abdomen

- B-NHL is often very responsive to chemotherapy

Lymphoblastic NHL: represent 30–35% of all pediatric NHL. I tis more common in adolescent age

- usually (90%) immature T phenotype, immunohistochemical positive T-cell markers (CD5,CD7)

- 50–70% of lymphoblastic NHL are localized at anterior mediastinum, tonsils, neck, supraclavicular or axillar area

- small fraction of lymphoblastic NHL develop from B cells, typical localization is neck adenopathy, skin or bones

Large cell NHL: represent about 15 – 20% of all pediatric NHL, it is a heterogeneous group, develop from mature B or T cells and is more frequent in adolescent age. In pediatrics mainly 2 subtypes :

-

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL): is the most common NHL in adults, in children is relatively rare – about 15% of all pediatric NHL

- in pediatric age is usually localized at mediastinum

- aggressive type of NHL, but curative with intensive treatment

-

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL): represent about 10% of all pediatric NHL, it is aggressive form of T –cell NHL

- express few T-cell surface markers (CD30, Ki-1)

- in pediatric age can appear in the skin, lungs, bones or other parts of the body

- 2 groups of ALCL with different prognosis depend on positivity or negativity of ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) . Patients with positive ALK expression have better outcome

Low grade NHL: are typical for adult age and are very rare in pediatric population. Typical representatives of low grade NHL are: follicular lymphoma, marginal zone/MALT lymphoma, primary CNS lymphoma or peripheral cutaneous lymphoma.

Bone marrow biopsy and lumbar punction

Bilateral bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy is standard part of initial work for necessity to evaluate % of blasts in bone marrow. A finding more than 25 % blasts in bone marrow is generally regarded as diagnostic of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Levels of blasts and lymphoma involvement less than 25% in bone marrow indicate clinical stage IV lymphoma

Any positive blasts in cerebrospinal fluid means CNS lymphoma infiltration and clinical stage IV.

Staging system

For pediatric NHL several staging systems have been proposed. The most acceptable and widely used is St Jude system (Figure 13).

Differential diagnosis

Depends on type and localization of the NHL:

Mediastinal mass:

- Other malignant lymphoma (Hodgkin lymphoma)

- Other malignant solid tumors (mediastinal germ cell tumor, neuroblastoma, sarcoma, thymoma, neuroendocrine tumor - carcinoid)

- Acute leukemia with mediastinal lymphadenopathy (CAVE - % of blasts in bone marrow)

- Aneurysma

- Benign thymus hyperplasia in small children

- Infectious process ( atypical pneumonia with reactive mediastinal lymphadenopathy)

Peripheral lymphadenopathy:

- Reactive lymphadenopathy

- Hodgkin lymphoma

- Infectious etiology, infectious focuses ( dental, skin or others)

- Zoonoses ( toxocarosis, thularemia, toxoplasmosis)

- Postvaccination reactive lymphadenopathy

Abdominal mass:

- Other malignant intraabdominal tumors (rhabdomyosarcoma, GIST, extraosseal Ewing sarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, neuroblastoma)

- Aggressive fibromatosis, neurofibromas

- Tumors of the adult age ( colon carcinoma, carcinoid, paraganglioma)

- Surgical cause of acute abdomen ( appendicitis, invagination, volvulus)

- Parainfectious mesenterial lymphadenitis

Skin localization:

- Infectious skin focus or infected insect bite

- LCH and non LCH histiocytosis (juvenile xantogranuloma)

- Cutaneous infiltration of acute leukemia

- Amelanocytic malignant melanoma

- Very rarely skin carcinoma (basocellular or spinocellular)

- Infected herpetic lesion

- Allergic or hypersensitive reactions

Therapy

Due to aggressiveness of biology behavior of pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphomas and risk of acute severe complications (tumor lysis syndrome, superior vena cava syndrome, acute renal failure, acute abdomen) all children suspicious from NHL have to be referred immediately to specialized pediatric cancer center.

Surgery

- The role of surgery in management of NHL is limited, the main role of surgery for NHL is diagnostic biopsy

- In a case of abdominal B-NHL presented as acute abdomen ( intestinal obstruction, invagination ) surgical intervention is indicated

- Radical resection (R0) of tumor mass is not required (NHL is systemic disease)

- Second look surgery is indicated in case of residual disease at the end of therapy

Chemotherapy

- Chemotherapy is the main treatment modality for NHL in children

- NHL is very aggressive tumor but with usually rapid response to chemotherapy (within some days) (Figure 14)

-

Dose intensity and duration of chemotherapy depends on

- histologic type of NHL

- clinical stage

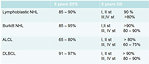

- risk group (Figure 15)

Radiotherapy

- radiotherapy is not a common treatment option and has only limited role in the treatment of pediatric NHL, most subtypes of pediatric NHL do not required radiotherapy

- for T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma with CNS infiltration low dose radiotherapy is used to treat neurologic symptoms

- radiotherapy should be used in palliative intention for patients with documented residual mass not responding to chemotherapy

Immunotherapy

Several monoclonal antibodies have been used in the treatment of adult NHL, but the use of immunotherapy in pediatric oncology has some delay. Probably this delay is caused by excellent results of standard chemotherapy for pediatric NHL. Currently two types of monoclonal antibodies are under investigation for pediatric age:

- rituximab (anti CD20 monoclonal antibody) for children with CD20 positive B-NHL

- brentuximab vedotin (anti CD30 monoclonal antibody) for ALCL

Prognosis and outcome

Prognosis of pediatric NHL improved significantly within the last decades and the most of the cases of pediatric NHL is curable. Generally more than 85% patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma survive 5 years. Outcome is affected by:

- advanced clinical stage (> 2)

- large tumor burden (LDH > 500 U/l)

- in pediatric studies age > 10 years is associated with inferior outcome

- residual tumor at the end of the treatment or relapse

- subtype of NHL (Figure 16)

- early response to chemotherapy

Author: Viera Bajčiová, MD, PhD