Special section Hodgkin lymphoma

Definition

Hodgkin lymphoma is a type of malignant disorder in which Reed-Sterberg cells are present in a characteristic background of reactive inflammatory cells of various types, accompanied by fibrosis of variable degree.

It was first described by Thomas Hodgkin in 1832.

In children and adolescents biology and clinical presentation of Hodgkin lymphoma is very similar to Hodgkin lymphoma in adult population.

There is age specific difference in the representation of the various subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma (lymphocytic predominance 2–7% in adults and only 20% in children).

Epidemiology

Hodgkin lymphoma account 5–6% of all malignancies in children under 15 years.

Peak incidence is in adolescent age (it is the second most common tumor in this age group and the most common malignant tumor in adolescent girls).

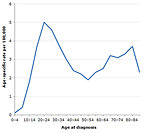

Annual incidence in adolescents is 3.45 per 100 000, but Hodgkin lymphoma is rare in children under 5 years (Figure 1).

Gender predominance varies within age: in small children (less than 5 years) virtually all affected are boys, in school age children and adolescents girls prevail.

Based on epidemiological studies three types of Hodgkin lymphoma can be expected:

- pediatric form in children younger than 14 years

- adolescents and young adults form (15–34 years)

- typical adult form (over 55 years)

Higher risk of Hodgkin lymphoma was observed in families with small number of children, the risk decreases with increasing number of older siblings.

Higher risk of Hodgkin lymphoma is also in families with high social-economic status.

There are race and ethnicity differences in incidence of Hodgkin lymphoma (white > black > Asians).

Etiology and etiopathogenesis

The cause of Hodgkin lymphoma is unknown.

Incorrectly indentified genetic predisposition is supposed, but not proven yet.

No definite link has been made with any virus or infection and Hodgkin lymphoma. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may be a trigger for developing Hodgkin lymphoma, it is positive in approximately 30% of children (EBV positivity is especially in mixed cellularity subtype of Hodgkin lymphoma, but almost never in lymphocytic predominance subtype), frequently in children younger 10 years.

Familial occurrence of Hodgkin lymphoma is very rare, but first degree relatives have five-fold increase in risk for Hodgkin lymphoma

Immunodeficiency (primary or secondary) has a higher risk of developing Hodgkin lymphoma (children infected HIV/AIDS virus, immunosuppressive therapy after organ transplantation…) or ataxia teleangiectatica.

Hodgkin lymphoma may occur as secondary malignancy in childhood cancer survivors.

No genetic predisposition syndromes are associated with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Clinical presentation and symptoms

Children with Hodgkin lymphoma may experience the following symptoms. Sometimes they do not show any of these symptoms or symptoms may be similar to symptoms of other medical conditions.

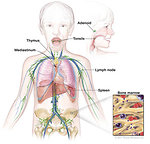

- Painless swelling of lymph nodes progressing in size, usually localized in the neck 80%), supraclav, axilla or groin is the first and most frequent symptom (Figure 2)

-

Approximately 25% of patients developed systemic symptoms (B):

- fever >38 °C initially of unknown origin, fever persist for days to weeks followed by afebrile intervals and then recurrence, no response to antibiotics. This pattern is called Pel Ebstein fever.

- night sweats

- unintended weight loss (>10% of body weight within the last 6 months)

- itching , general weakness, fatigue, tiredness

- Mediastinal lymph nodes are affected in 60–75% of cases (mostly in adolescents), usually patients are asymptomatic, about 20% of patients have massive mediastinal involvement – so called bulky disease (mediastinal mass ratio greater than one-third of the intrathoracic diameter and/or nodal mass over 10cm in diameter)

- Symptoms related to mediastinal mass are dry cough, later on dyspnea

- Superior vena cava syndrome caused by tumor mass compression of vena cava superior is not usual as initial symptom

- Infradiaphragmatic lymph nodes or organ involvement is less frequent in children than in adults

- Less than 15–20% of patients develop extranodal disease (spleen, liver, lung, bone, bone marrow)

Diagnostic procedures

Physical exam: special attention must be paid to the lymphatic system – (Figure 3), all nodal areas as well as abdominal and groin palpation. Involved lymph nodes are not painful or tender, but have a “rubbery” firmness to palpation. Although Waldayer’s ring involvement is infrequent, it may present as asymmetric tonsillar enlargement – (Figure 4). Thus examination of the nasopharynx, oropharynx is important.

Laboratory tests: there is no specific blood test that indicates Hodgkin lymphoma. Tests include:

- hematology tests:: ESR, CBC, coagulation profile elevated ESR is common and useful marker of disease activity

- biochemistry: liver and renal function tests, ALP, CRP, LDH, ferritin, serum copper. AFP is non-specific indicator of disease activity, serum copper is useful as an indicator of relapse

Imaging studies: because Hodgkin lymphoma tends to spread from one lymph node group to the next adjacent group, imaging tests are used to find out the extent of spread of the disease.

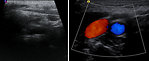

- Ultrasound of the involved lymph nodes is usually the first imaging study. Ultrasound can show the structure of lymph nodes, areas of necrosis, vascularity and L/T index. Echocardiography can evaluate pericardial effusion (Figure 5).

- Chest X-ray is essential in all cases (posteroanterior and lateral). It is important to measure and define bulky disease (Figure 6).

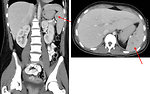

- CT scan the major value of CT scan is in the detection of subtle mediastinal adenopathy when the chest X-ray looks normal. Pericardial, retrocardial mass or pulmonary parenchyma/chest wall involvement can be discovered on CT scan of the chest (Figure 7). Abdominal CT scan is helpful to detect nodal as well as extranodal infradiafragmatic involvement (spleen, liver, kidneys) (Figure 8).

- 18 FDG PET scan is based on fact that cancer cells absorb glucose more quickly than normal cells so they light on PET scan. Initial PET scan is used to verify extent of disease in the whole body and measure activity in the tumor involved areas (SUV). Currently PET scan is mandatory for tumor response evaluation – PET scan after the first course of chemotherapy divide patients into two groups – rapid early responders or slow early responders, which is crucial for further treatment strategy. It is also useful for follow up study to evaluate residual masses, diagnosis of early recurrence and prognosis. Specificity of PET scan is about 90–95% (Figure 9).

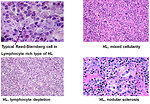

Histopathology: the common histology feature of Hodgkin lymphoma is Reed-Sternberg cells (RS cells). Most current studies indicate that the RS cells of Hodgkin lymphoma are lymphocytic in nature and, in the great majority of cases, are of B-cell origin. RS cell is typical large cell with classically binucleate – typical “owl eye appearance” (Figure 10). Several classifications have been used for Hodgkin lymphoma historically. Since 2008 WHO classification has divided Hodgkin lymphoma into two main groups. Subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma are age related and also may correlate with certain patterns of disease (Figure 11, 12).

-

classic Hodgkin lymphoma – 4 subtypes:

- lymphocyte rich: is often associated with localized cervical or inguinal localization

- nodular sclerosis: is the most common type in adolescent group of patients, usually present as mediastinal mass

- mixed cellularity: is typical for pre-pubertal age group and usually advanced disease

- lymphocyte depletion: is rare in pediatric oncology

- nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma

Bone marrow biopsy: Hodgkin lymphoma rarely spread to bone marrow (overall BM involvement is about 5%). Nonetheless bone marrow biopsy is recommended for patients with B symptoms, clinical evidence of subdiaphragmatic disease, advanced stage of disease or in a case of clinical suspicion (aneamia, leucocytosis or leucopenia and thrombocytopenia in peripheral blood).

Differential diagnosis

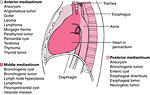

Mediastinal mass (Figure 13):

- Other malignant lymphoma (non-Hodgkin lymphoma)

- Other malignant solid tumors (mediastina germ cell tumor, neuroblastoma, sarcoma, thymoma, neuroendocrine tumor - carcinoid)

- Acute leukemia with mediastinal lymphadenopathy

- Aneurysma

- Benign thymus hyperplasia in small children

- Infectious process ( atypical pneumonia with reactive mediastinal lymphadenopathy)

Peripheral lymphadenopathy (Figure 14):

- Reactive lymphadenopathy

- Infectious etiology, infectious focuses ( dental, skin or others)

- Zoonoses ( toxocarosis, thularemia, toxoplasmosis)

- Postvaccination reactive lymphadenopathy

Therapy

Surgery:

There is no role for surgery as a treatment approach for Hodgkin lymphoma, except of Hodgkin lymphoma nodular lymphocyte predominant type localized form (stage I), when surgery has also therapeutic aim.

Open surgical biopsy and extirpation of lymph node is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer.

Fine needle aspiration biopsy is not recommended and open biopsy is a standard of care.

Historic so called staging laparotomy is currently does not indicated.

Chemotherapy:

Chemotherapy is always used as treatment modality in Hodgkin lymphoma in children

Treatment strategy is based on:

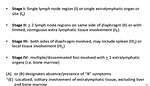

- clinical staging (Ann Arbor) (Figure 15 a 16)

-

risk classification according to clinical staging and symptoms (Figure 17):

- A - not present

- B - present

- early response to chemotherapy:

-

after the first course of chemotherapy the further management depends on response-based strategy evaluated by PET scan:

- RER – rapid early responders may have a reduction of chemotherapy as well as radiotherapy

- SER – slow early responders may have more intensive chemotherapy and standard dose of radiotherapy

Classic combination of chemotherapeutic agents used for Hodgkin lymphoma in pediatric oncology is DBVE (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastin and etoposide).

For advanced stage cyclophosphamide and prednison are added (DBVE-PC).

Patients having nodular lymphocyte predominant form of Hodgkin lymphoma are treated as a special group that require the least aggressive treatment.

Radiotherapy:

Pediatric approach for radiotherapy used low dose and reduce volume of radiotherapy compared with traditional regimens.

Standard radiation dose for children and adolescent is 21 Gy.

Reduced volume means radiotherapy to only involved areas (involved field radiotherapy) (Figure 18, 19).

Need for radiotherapy is determined both stage of disease and response to chemotherapy .

Currently some clinical trials in pediatric oncology are in progress to identify group of low risk patients with rapid early response to chemotherapy that they may not need radiotherapy as well (Figure 20).

The main goal is to reduce the amount of radiotherapy to ovoid late effects without affecting the overall survival.

Prognosis and outcome

Prognostic factors:

- clinical stage (extent of disease)

- positive B symptoms

- positive bulky disease and extranodal involvement

- subtype of Hodgkin lymphoma

- early response to chemotherapy on PET scan

Negative prognostic factor in adolescents older 15 years is male gender.

5 years overall survival for Hodgkin lymphoma is more than 95% of cases.

Very important point of pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma is risk of serious late effects and consequences after treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma – cardiotoxicity, pulmonary toxicity, hypothyreosis, gonadal toxicity and secondary malignancies (especially breast cancer in girls, thyroid cancer and leukemias).

Author: Viera Bajčiová, MD, PhD